In 19th century America, Walt Whitman dreamed of unlocking the potential in every man’s heart to love other men. He did not envision male same-sex attraction as a minority phenomenon.

“Whitman knew that capacity for same-sex love lies in every man’s heart. He had seen it and experienced it firsthand in the war hospitals. It was only what he saw as anachronistic social impositions, fear and lack of knowledge, that prevented men from freely expressing what was in their hearts. He set himself to free American young men from those fears and repressive structures.” Juan A. Herrero-Brasas. ‘Whitman’s Church of Comradeship Same-Sex Love, Religion, and the Marginality of Friendship.’ in QUEER RELIGION VOL 1

Whitman certainly didn’t hide his affection for his male companions:

When I saw the full moon in the west grow pale and disappear in the morning light,

When I wandered alone over the beach, and, undressing, bathed, laughing with the cool waters, and saw the sun rise,

And when I thought how my dear friend, my lover, was on his way coming,

O then I was happy;

O then each breath tasted sweeter—and all that day my food nourished me more—

And the beautiful day passed well,

And the next came with equal joy—And with the next, at evening, came my friend;

And that night, while all was still, I heard the waters roll slowly continually up the shores,I heard the hissing rustle of the liquid and sands, as directed to me, whispering, to congratulate me,

For the one I love most lay sleeping by me under the same cover in the cool night,

In the stillness, in the autumn moonbeams, his face was inclined toward me,

And his arm lay lightly around my breast—And that night I was happy.

(From When I Heard at the Close of the Day)

But he emphasised also how this love brought him transcendent feelings and a vision to match:

From Song of Myself:

I mind how once we lay, such a transparent summer morning,

How you settled your head athwart my hips and gently turned over upon me,

And parted the shirt from my bosom-bone, and plunged your tongue to my bare-stript heart,

And reached till you felt my beard, and reached till you held my feet.

Swiftly rose and spread around me the peace and knowledge that pass all the argument of the earth,

And I know that the hand of God is the promise of my own,

And I know that the spirit of God is the brother of my own,

And that all the men every born are also my brothers, and the women my sisters and lovers,

And that a kelson of creation is love.

From the Calamus poems:

The most dauntless and rude shall touch face to face lightly,

The dependence of Liberty shall be lovers,

The continuance of Equality shall be comrades.

These shall tie and band stronger than hoops of iron,

I, extatic, O partners! O lands! henceforth with the love of lovers tie you.

I will make the continent indissoluble,

I will make the most splendid race the sun ever yet shone upon,

I will make divine magnetic lands.

With the love of comrades,

With the life-long love of comrades.

I will plant companionship thick as trees along all the rivers of America,

and along the shores of the great lakes, and all over the prairies,

I will make inseparable cities, with their arms about each other’s necks.

By the love of comrades,

By the manly love of comrades.

For you these, from me, O Democracy, to serve you, ma femme!

For you! for you, I am trilling these songs.

Writer Paul Zweig, in Walt Whitman: The Making of the Poet (1984) was of the opinion that, “At times Whitman’s attraction to men seemed to rule his character and his thinking. The “Calamus” poems are lucid rhapsodies of love and loss. They are among the finest love poems in our language, and they are addressed to a man. With “Song of Myself,” “Calamus” became a cornerstone for all the future editions of Leaves of Grass. It is a culminating moment, when Whitman’s ineradicable feelings were reinforced and clarified by a political theme. In “Calamus,” Whitman saw “Democracy” as a fluid, lawless, yet orderly exchange of feelings among “comrades,” a network of intimacies on a vast scale. “Democracy” could succeed only as an unimpeded flow of love, of which he, Walt Whitman, would give the first example, with the open-toned utterance of his truest feelings. The poems of “Calamus” grounded Whitman’s vision and gave it a wholeness. Intense love between men became, for Whitman, the fundamental bond.”

David Kuebrich stated, in his 1989 book Minor Prophecy: Walt Whitman’s New American Religion, that Whitman’s work is “not a gospel of homosexuality but of mystical love.” I would like to point out that, actually, homosexuality is mystical love — a fact some queer men have known since at least the 4th century BCE when Plato wrote about it in the Symposium.

English writer John Addington Symonds attempted in correspondence with Whitman to get the poet to expressly declare that his poetry celebrates erotic relationships between men. Whitman refused, claiming that he had fathered several children. Whitman was bisexual, as the conversation below between Gavin Arthur (lived 1900-1972), a San Francisco astrologer, author of 1966 book The Circle of Sex, and English philosopher Edward Carpenter reveals. Carpenter had spent time with Whitman in the US and knew him intimately. Gavin recorded this conversation, which had taken place in 1924, at the request of Allen Ginsberg, in 1967. It was published in the Gay Sunshine Journal in 1978.

Gavin Arthur: I was 23 and came up the garden path with the letter of introduction awkwardly in my hand. He seemed to know I was coming for he opened the door and held out his arms. “Welcome my son” he growled affectionately as if he had known me for ever. He did not read the letter but drew me into the cozy study by the fire and introduced me to his comrade George [Merrill] and George’s comrade Ted. George was about 60 and was pouring tea. Ted was about 40 and was sticking flowers in a vase. Both were warm in their welcome. I was about 20 and Carpenter about 80…

I asked him if he had ever been to bed with a woman and he said no–that he liked and admired women but that he had never felt any need to copulate with them. “But that wasn’t true of Walt, was it?” I asked.

“No, Walt was ambigenic,” he said. “His contact with women was far less than his contact with men. But he did engender several children and his greatest female contact was that Creole in New Orleans. I don’t think he ever loved any of them as much as he loved Peter Doyle.”

“I suppose you slept with him?” I blurted out half scared to ask.

“Oh yes–once in a while–he regarded it as the best way to get together with another man. He thought that people should ‘know’ each other on the physical and emotional plane as well as the mental. And that the best part of comrade love was that there was no limit to the number of comrades one could have–whereas the very fact of engendering children made the man-woman relationship more singular.”

“Had he no interest in bringing up his own children–in the husband-father relationship?”

“No. He said his women had been married to men of wealth and social standing who could not engender children of their own, but who wanted the children Walt engendered to regard them as father. He said he felt that his mission as Answerer did not require specific paternity and that all the young men of America were his spiritual sons and all the young women his spiritual daughters.”

“How did he make love?” I forced myself to ask.

“I will show you,” he smiled. “Let us go to bed.”

If you would like to read what happens next: Gay Sunshine

‘Comradeship was, for Whitman, a complex and multifaceted theme in both his life and his poetry. He conceived of it as a crucial form of religious experience which provided humans with an existential sense of God’s presence in this world and living proof of a transcendent spiritual realm and the soul’s immortal destiny. On a political level, comradeship was to elevate the male personality and refine its coarser elements, creating an unprecedented male intimacy and bonding that would unify the United States citizenry (for Whitman, politics remained largely a male preserve) and create new forms of international solidarity.

‘Whitman always conceived of comradeship as an essential feature of his religious vision. In “Starting from Paumanok,” written in conjunction with “Calamus,” he describes “two greatnesses,” love and democracy, which are informed by a “third one rising inclusive and more resplendent,” that is, the “greatness of Religion.” In “Calamus” itself, Whitman gives primary emphasis to the spiritual meaning of “manly love.” It is the love of comrades, he announces in the opening poem, rather than “pleasures, profits and conformities,” which he needs to “feed” his “soul” (“In Paths Untrodden”). This theme is further established in the second poem as Whitman affirms that the experience of loving comradeship raises his soul to a heightened state (“how calm, how solemn it grows to ascend to the atmosphere of lovers”) and instills in him a sense of integration into a more real spiritual order: the “real reality” which transcends the natural world, making it, in comparison, seem but a mere “mask of materials” or “show of appearance” (“Scented Herbage of My Breast”). Elsewhere in the sequence he also calls attention to how friendship culminates in a spiritual love that is part of a higher spiritual reality, referring, for example, to how it liberates his soul so that, becoming “disembodied” and “[e]thereal,” it “float[s] in the regions” of spiritual love (“Fast Anchor’d Eternal O Love!”).’

Whitman’s vision, inspired by love of other men, was absolutely non-dual:

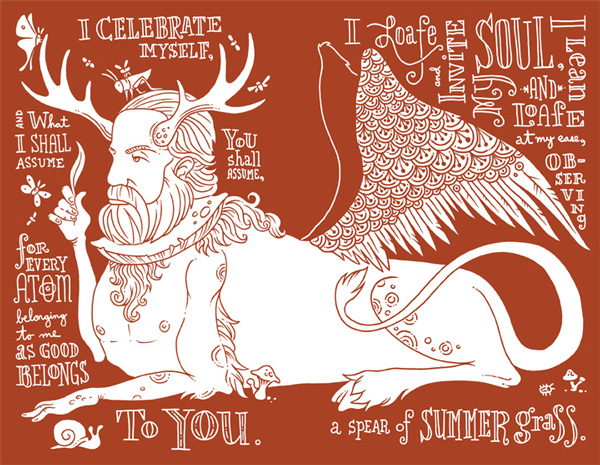

“I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.”

Whitman’s vision of love between men, of comradeship, as a force for peace in the world, as a necessity if we hare to have true democracy, could change the world. He was calling to men to open their hearts and minds and bodies to each other, not to the exclusion of women, not to create a separate social group, but in order that they might open their eyes to the greater divine reality, and so bring peace and prosperity, harmony and hope to the world.

It was while as a nurse working with wounded soldiers in the American Civil War that Whitman’s heart opened and vision formed.

“In the extreme emotional intensity (thus, in the dense marginality) provided by the war hospitals, Whitman came to believe that the desire for physical and romantic male-to-male affection lies in every man’s heart even though most men may be themselves unconscious of it.” Juan A. Herrero-Brasas

How many more must die before men refuse to kill each other and choose to love each other instead? When we will see brother instead of other?